We Do it Together or Not at All

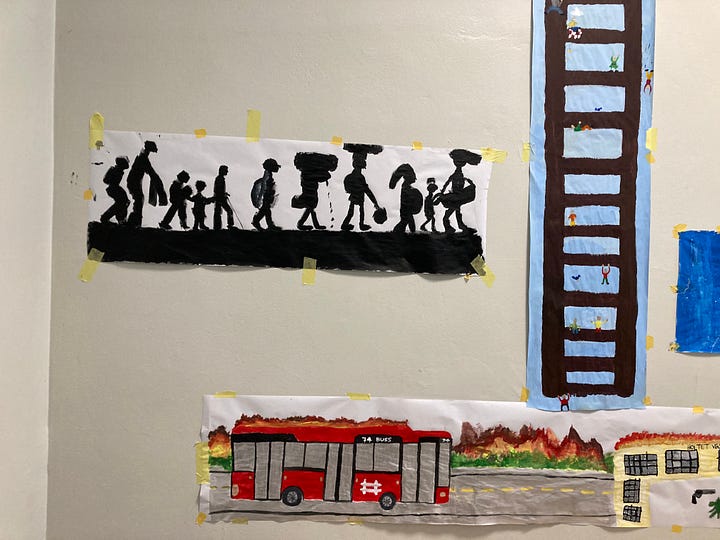

This week I finished my first personal mural project. Together with around 80 teenagers from a local high school, we painted an indoor mural measuring approximately 35 x 2.5 meters over seven days. The project was funded by SKUP, which is a research and school-development project led by Oslo Met University College and Den Kulturelle Skolesekken (a publicly funded art and culture program for kids in school), in collaboration with schools and artists.

I’ve been working with the school since January, doing a series of different workshops teaching the kids different street art techniques and ways of self-publishing. My goal was to create a collective artwork, where the kids felt comfortable taking part in the creative process, and in the actual production of the artwork. I didn’t want it to be “my” mural, but ours. I knew I had very little time to do everything I needed to get done for that to happen. I had to get an impression of their skills to be able to come up with a plan for the artwork, and I needed to create an atmosphere where they felt like they could try something out and explore different forms of self-expression.

To make this process even more challenging, there were five different classes involved in this project. The kids in three of the classes were studying to become paramedics, and the kids in the other two classes were young people who had recently arrived in Norway from other countries like Iran, Yemen, Ukraine, Moldova, Eritrea, Somalia, and more. And broadly speaking, these are two groups of students who usually don’t interact that much in a school setting.

The school had in advance decided that the theme of the project should be “escape”, and my job to lead the process of creating something together with 80 students.

It’s the most challenging art-project I’ve ever done. And I am so incredibly proud of how it all turned out. In my line of work, I have to move fast, and I am constantly working on several different projects at the same time, trying to secure funds to be able to not only make them happen, but also to be able to pay my rent. There is little to no security, but there is freedom.

In a school system, there’s this constant battle going on, between making sure that the kids are learning the things society and government have decided that they have to know, and what the kids themselves want or could have wanted to learn. How do we teach children to learn, and not only teach them what “we” want them to know? How is the skill “to learn” taught?

My academic background is in social pedagogy:

a holistic and relationship-centred way of working in care and educational settings with people across the course of their lives. In many countries across Europe (and increasingly beyond), it has a long-standing tradition as a field of practice and academic discipline concerned with addressing social inequality and facilitating social change by nurturing learning, well-being and connection both at an individual and community level.

The term 'pedagogy' originates from the Greek pais (child) and agein (to bring up, or lead), with the prefix 'social' emphasising that upbringing is not only the responsibility of parents but a shared responsibility of society. Social pedagogy has therefore evolved in somewhat different ways in different countries and reflects cultural and societal norms, attitudes and notions of education and upbringing, of the relationship between the individual and society, and of social welfare provision for its marginalised members.

Social pedagogues (professionals who have completed a qualification in social pedagogy) work within a range of different settings, from early years through adulthood to working with disadvantaged adult groups as well as older people. To achieve a holistic perspective within each of these settings, social pedagogy draws together theories and concepts from related disciplines such as sociology, psychology, education, philosophy, medical sciences, and social work

One of the most influential pedagogical books I read during my education, is The Pedagogy of the Oppressed, by Paolo Freire.

It’s a short book, only about 150 pages, but don’t let that fool you. It’s easy enough to read, I’ve read it several times, but every time I do, I learn something new. I wouldn’t know where to begin to summarize it, but perhaps Assata Shakur can:

The schools we go to are reflections of the society that created them. Nobody is going to give you the education you need to overthrow them. Nobody is going to teach you your true history, teach you your true heroes, if they know that that knowledge will help set you free.

One of the biggest lessons from Freire for me, was to understand how shallw our society’s understanding of freedom from oppression is, and how to overcome it. Liberation does not mean to leave the position of being oppressed, only to take the position of the oppressor; it means, to break the systems of oppression. In our society, in our competitive individualistic culture, we teach kids to be the best, and become “winners”. But the only thing that competitions creates that can’t be achieved through cooperation and solidarity, is losers. For someone to win, someone has to lose. And we are presented with this dichotomy as the only possible solution, but it’s a lie. It’s the only possible solution for this society, it’s in fact the only way to maintain it, but it doesn’t mean that we can’t do it differently.

Paul Natorp was one of the first key thinkers of social pedagogy, and one of his teachings serves as a theorem for me. He wrote that humans become human through human interaction. Which is one of the reasons why I will fight any and all forms of dehumanization. Freire also writes about this:

In the first chapter, Freire outlines why he believes an emancipatory pedagogy is necessary. Describing humankind's central problem as that of affirming one's identity as human, Freire states that everyone strives for this, but oppression prevents many people from realizing this state of affirmation. This is termed dehumanization. Dehumanization, when individuals become objectified, occurs due to injustice, exploitation, and oppression. Pedagogy of the Oppressed is Freire's attempt to help the oppressed fight back to regain their lost humanity and achieve full humanization. Freire outlines steps with which the oppressed can regain their humanity, starting with acquiring knowledge about the concept of humanization itself.

We live in a time where dehumanization is not just an “unfortunate” consequence, but a requirement for the continuation of the status quo to protect the power of the oppressors (the richest and subsequently most powerful people in terms of weapons). It would not be possible to maintain our way of life here in the global north and west, were it not for the exploitation of people and natural resources in other countries. The same systems are the reason why people are forced to leave their homes to try and find a safe place to live. And if that wasn’t bad enough, we have the audacity to refuse them entry, and let them die as they cross the seas.

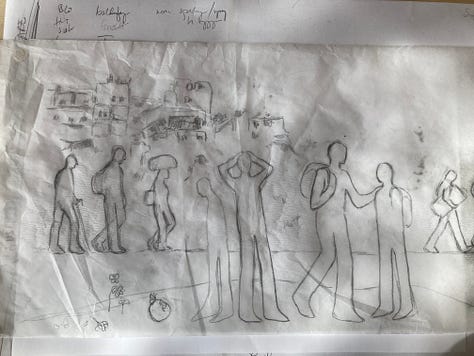

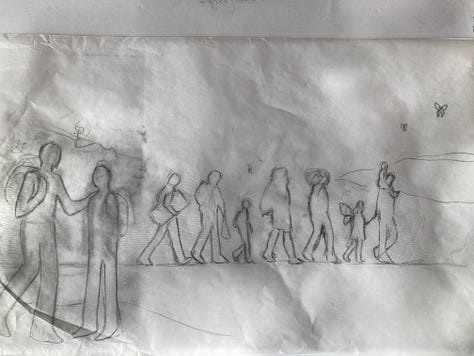

I wanted to let the kids tell me what they wanted to create, and let them define how we should work with the theme “escape”. So first we worked with how to use symbolism in art, and colors, styles, to help express our message visually. I then asked them to bring me pictures or song texts, poems, about the topic we were working on, and asked them to make sketches based on them.

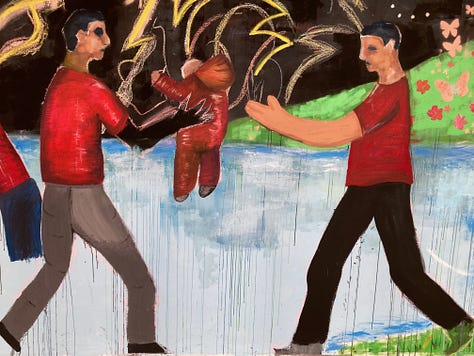

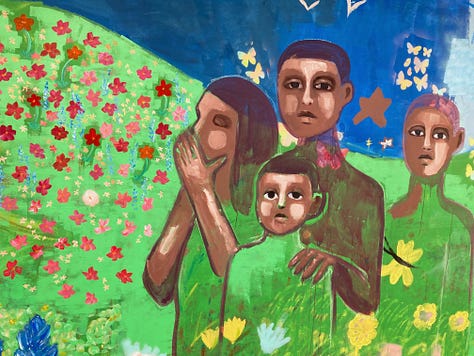

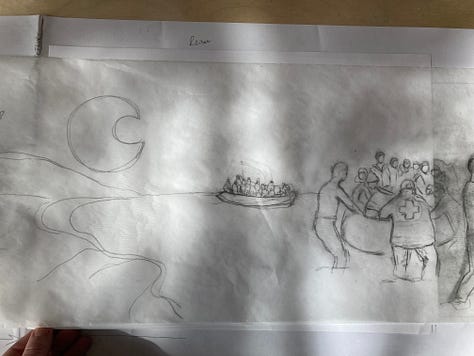

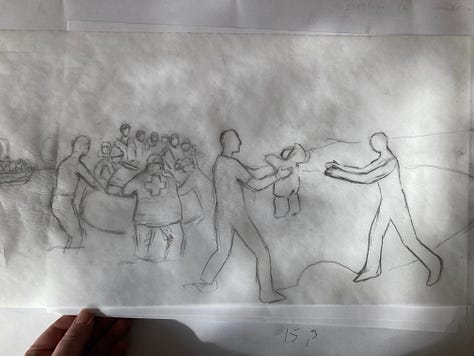

Based on these paintings, their reference photos, texts, and previous workshops, I made a sketch to include as many of the ideas they had as possible into the narrative that I kept seeing and hearing from the kids, about having to leave an unsafe place in search of a safe place, symbolized through the journey of refugees, or migrants, that we for some reason have accepted as a term. Many of the pupils brought photos or drew refugees on boats, and so I decided to make that the main story, and also added the paramedics and ambulances, which seemed fitting considering three of the classes were studying to become paramedics.

I tried to make the sketch as open and simple as possible, but still beautiful and true to their ideas and the story that they wanted to tell. And then I showed it to them to ask for their feedback and approval. Once we agreed, the most intense two weeks of production I have ever experienced began.

I wanted more than anything for them to feel proud of what we were making together, and I was not sure if I would be skilled enough or work fast enough to be able to make everything come together.

For those of you who know me, or have been a reader of my work, you might remember that one of my goals last year working towards my exhibition in January, was to push myself to work faster. I didn’t know at the time that this project was coming my way, but boy am I happy that I had trained on painting quicker and with more confidence, because I really appreciated having put such an effort into that area when starting this mural. 35 x 2.5 meters is after all a big canvas, and I didn’t know if I had been able to create enough trust from the students in me and each other to show up and add their voices to the mural. Most of them hadn’t painted or drawn in years before we began the workshops in February (don’t get me started on the position of arts and crafts in school, because it is insane to me how underfunded and undervalued this is), and they were asked to paint in front of EVERYONE at their school. That’s a pretty vulnerable thing to do as a teenager (or at any age, really). The courage they showed me, in showing up, and giving it their best, will stay with me as some of the most profound moments of my life. I am proud beyond words of their effort and heart. And so very grateful.

There is a power to art, to creation, that cannot be overstated. To be able to think something up, and make whatever it is real, creating something that never was until it is made, must be one of the most human of human qualities. We value this ability so much so that when humans created god, they even created god to be a creator. That’s why whenever people tell me they would never be able to make art, I tell them that they need to question what art is, in stead of their ability to make it.