I made this installation, DISOBEY/DISRUPT, in honor of the student’s intifada at the American universities, after president Biden’s remarks about how dissent should not lead to disruption. I think often of Martin Luther King Jr who said, “riot is the language of the unheard”, because it’s about power and who has enough of it to define reality. And even if it’s been almost 30 years since I read 1984, I recognize Biden for what he’s doing.

I had a conversation the other day with a woman that I hadn’t met before, and I was telling her a little about my subversive art practice and the stuff I do without asking anyone else’s permission. I had just written a text for an independent magazine, Torggata Blad, about this substack, which was the context of our conversation. We discovered we both had similar experiences as social workers, an occupation we both had to leave, because the system was eating us and the people it was supposed to help alive, and I was telling her about how subvertising changed my life.

The published text is in Norwegian, but I’ve translated a section from it here:

"I wasn't really alone until I was 35. That's when I left mortgages and car loans and Friday trips to Ikea, display cabinets filled with crystal glasses for three-course dinners for twelve, complete with dog, garden, and dysfunctional in-laws in every direction. A few years later, I left the permanent full-time position I had working with child welfare in the municipality, which would have been mine for the rest of my working life. Because I could no longer ask of those who were most harmed by society being as it is, to “work on themselves”, in the hope that they one day might be let back in by the same people who pushed them out in the first place. It made me sick.

I cried every single day for almost a whole year after I quit, I was completely exhausted, and didn't know what to do with any of the things that made me that way except to rest. Then in May 2019 I was randomly invited to a workshop by someone I didn't know, who ran Subvertising Norway. I made my first poster, and saw my first piece of street art installed without asking anyone's permission first, and that was it. Something had changed forever.”

https://torggatablad.no/selvhjelpsarkivet/

The woman asked, “you must be very unafraid to do the things that you do?”. And I said, “no, not really, I’m just… a white Norwegian. What are they going to do to me? They can’t throw me out, and if they want to throw me in jail, it’s going to be because I fight for freedom of expression and I don’t have enough money to pay a fine. That’s not going to be a very good look for either the ad companies or the government. And I know that it’s different for Norwegians who have darker skin than me, or who live here without permanent residency, and that’s why people like me HAVE to do stuff like this. So I’m not at all fearless when it comes to this, I’ve just calculated the risk and balanced it with my privilege, and made a choice”. The woman, who had a different skin color than mine, was quiet for a moment before she initiated a candid conversation about racism, on a personal and systemic level.

Back in 2022, for International Women’s Day, I made an installation using an advertising poster for some winter-sport competition that was going to be aired on television, with two incredibly ‘norwegian’ looking people. The ad just made me really mad, because we here in Norway like to think ourselves not only physically superior when it comes to cross country skiing, but also morally superior, because it’s unthinkable to us that any of the athletes representing Norway would ever use any sort of performance enhancing methods or drugs. Which of course is not true, or even believable at any statistical or logical level, but if you voice any doubts about that, you are not a good sport or a good Norwegian. We don’t have to cheat you see, because we are just that good.

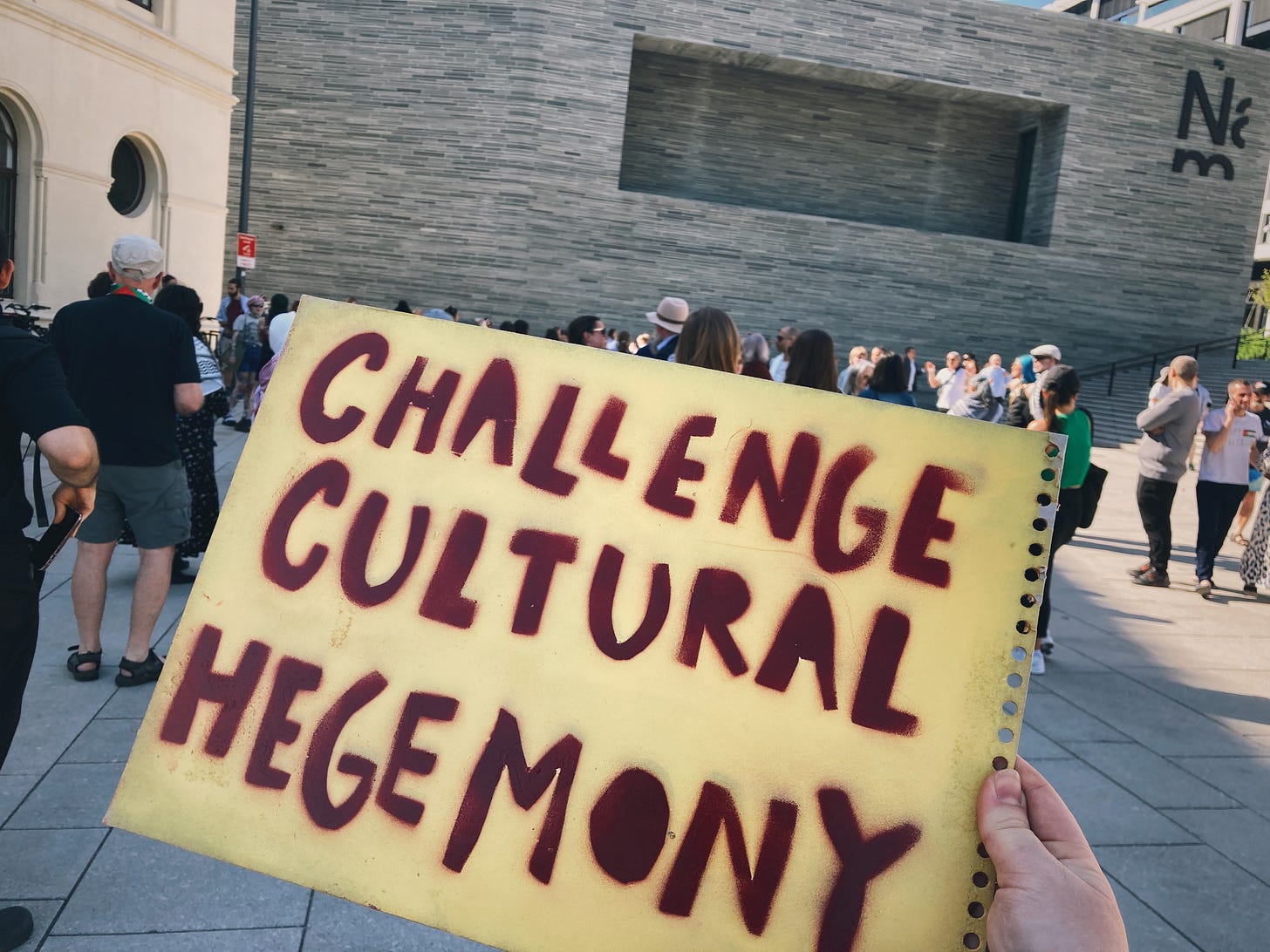

It’s one thing to aspire to live up to our ideals and the stories we tell ourselves about who we want to be - and can be, but it’s quite another to turn a blind eye to reality as a way to protect our own privileged position. So I cut out the text “Challenge Cultural Hegemony - Make Space For Us All”, and that became sort of a mission statement for me. It guides a lot of my choices when it comes to working with art and culture.

In Norway, we celebrate every year the signing of the constitution in 1814, on May 17th, with a children’s parade. Here in Oslo, the big finale is to wave at the king and the royal family up on the royal castle’s royal balcony. The king of Norway has a lot of symbolic and cultural power, as well as constitutional power. He’s not part of the government, but he still signs off on the decisions made by them in the King’s council, and is the one who declares parliament to be in session each autumn. We are very proud to have a kind king, and he’s a really nice guy, I have to say, but it still doesn’t sit right with me, the whole parading of the children in front of the castle.

We are also very pleased with ourselves and the fact that we celebrate our nation by making it a day for the children. We don’t parade our military, or our weapons, instead we center the future, our kids. Personally I’m very ambivalent about this. Because on one side I love that we celebrate our youths. But on the other side, it also makes it very difficult to question the whole concept without being labeled a grinch. Any concerns about this cultural indoctrination of patriotism and nationalistic pride (and privilege) in children are invalidated almost immediately, and very easily if someone like me raise them, since I’m a single woman in my mid-forties without children.

This is a very effective way to silence any critique from people who live outside the norm and question the cultural hegemony of any society:

In Marxist philosophy, cultural hegemony is the dominance of a culturally diverse society by the ruling class who shape the culture of that society—the beliefs and explanations, perceptions, values, and mores—so that the worldview of the ruling class becomes the accepted cultural norm. As the universal dominant ideology, the ruling-class worldview misrepresents the social, political, and economic status quo as natural, inevitable, and perpetual social conditions that benefit every social class, rather than as artificial social constructs that benefit only the ruling class.

If you aren’t successful, you can’t be taken seriously when you critique the system, because you are probably just mad that you aren’t successful.

I didn’t take part in any celebration for the constitution of this country this year, because since October 2023, it has become very clear that there’s two separate sets of rules when it comes to warfare and human rights, and it is based on racism. I didn’t feel comfortable celebrating a legal obligation to protect basic human rights that we are not taking seriously. I didn’t wear my beloved bunad on 17th of May, handmade by my late paternal grand mother Kari, with the silver lily broche chosen especially by my maternal grand mother, Lily, gifted to me by my parents and their parents for my confirmation when I was 15. It’s the most precious thing I have. It’s my heritage, where I come from, where I belong, and when I wear it, I feel at home in a way that I can’t explain in words.

Instead, I wore it for the 18th of May, to protest the National Museums sudden inability to reflecting the times and engage with the war on Palestine, because that’s a political issue. As if art isn’t incredibly political. I read once something that really stuck with me, about how the purpose of culture is to maintain status quo, while the purpose of art, is to disrupt it.

On my way to the protest, I was walking by a lot of people who looked at me funny because I was wearing my bunad a day too late. And then there was this couple, who looked at me with disgust. I was wearing my keffiyeh with my bunad, and even if I couldn’t make out their exact words, the hate was written all over their face. Their expression was completely different from the others who looked either puzzled, confused or amused. And I thought back on all the times I’ve been told by people about the racism they experience in this city, and how they so often are met with disbelief and attempts to rationalize away their painful experience. Eventually they just stop telling us (white people) about it, because what’s the point if we are just making excuses for the people who hurt them?

We say things like they probably misunderstood or misread the situation, and we even blame them, saying that since they’ve had bad experiences in the past, perhaps they read too much into it…? As if a darker skin color somehow makes you less able to read peoples expressions and body language. As if it isn’t infinitely more likely that having to navigate a white society with a darker skin color has taught you how to be an expert reading people’s intentions, in order to stay safe. Honestly, the inability applying common sense when it comes to these situations still baffles me, and reveals at the same time the cultural bias that makes racism invisible to us. Yes, trauma will affect how you experience the world, but are still we somehow under the impression that not acknowledging pain will simply make the problem go away?

I do not consider myself done when it comes to unlearning oppression and privilege, I’m not cured of it and I probably never will be, but I am committed to try and learn and unlearn. It’s a choice that I make, to seek out knowledge, to question what I think I know, and to try my very best to listen when I feel uncomfortable. One of the teachings I’ve taken with me from my days as therapist and social worker is how important it is to stay with the discomfort, and to sit with it in stead of rushing to make it go away as we naturally tend to do. Discomfort is information, if you learn how to read it. And so is disobedience and disruption. Don’t be so quick to silence it.

Maybe your illusion of having control needs to break in order for you to get to where you need going.